For as long as humans have walked the earth, we have looked up and wondered: what if? What if we could slip the bonds of gravity and soar like the birds? What if we were never meant to be earthbound at all?

Across centuries and cultures, myths, experiments, and lost histories paint a picture of an ancient world obsessed with flight. From doomed gliders and forced kite experiments to celestial airships in Hindu epics, the dream of taking to the skies predates the first successful flights by millennia.

And perhaps—just perhaps—someone, somewhere, succeeded before we ever knew it.

Early Flight Experiments: Bold, Brilliant, and Bone-Breaking

The 9th Century Scientist Who Nearly Flew

In 9th-century Andalusia, a polymath named Abbas ibn Firnas stood atop a tower in Córdoba, his body covered in vulture feathers, artificial wings strapped to his arms. Before a crowd of onlookers, he leaped into the air.

For a moment, he flew.

He managed to glide a significant distance, proving that controlled descent was possible. But as he hurtled toward the ground, the truth became clear—he had mastered the lift, but not the landing. He crashed, surviving with injuries and later lamenting that he had not studied how birds land.

Aside from his ill-fated flight, ibn Firnas was a renowned scientist, engineer, and astronomer. He constructed an early planetarium, devised a method for making colorless glass, and even developed reading lenses centuries before spectacles became common. But his dream of flight would inspire others to follow.

.

Eilmer of Malmesbury: The Monk Who Flew Too Far

Two centuries later, in 11th-century England, a Benedictine monk named Eilmer of Malmesbury attempted something strikingly similar.

Strapping large, wing-like structures to his arms, he leaped from the tower of Malmesbury Abbey and glided nearly 200 yards—an extraordinary distance for an uncontrolled flight. But, like ibn Firnas, he hadn’t accounted for landing. The crash broke both his legs.

Later, Eilmer reportedly mused that he could have succeeded if only he had added a tail for stability—an insight that foreshadowed the very principles of modern aerodynamics.

A Chinese Experiment in Human Flight—at a Deadly Cost

Flight experiments weren’t always voluntary. In 559 A.D., Emperor Wenxuan of Northern Qi allegedly forced several prisoners to participate in a cruel experiment. Strapping them to enormous kites, they were launched from a tower to see if they could glide.

Only one man, Yuan Huangtou of Ye, is said to have survived. His reward? Execution.

This tale is shrouded in mystery, but if true, it would be one of the earliest recorded cases of a human gliding flight—albeit under horrific circumstances.

From Myth to Machine

Even before real-world attempts, humans imagined flight long before they understood it. Myths and legends across cultures tell of humans defying gravity in ways that eerily resemble early aeronautical theories.

Icarus and Daedalus: A Cautionary Tale or an Echo of a Forgotten Past?

One of the most famous flight myths comes from Greek mythology. Daedalus, a master craftsman, constructed wings of wax and feathers for himself and his son, Icarus, so they could escape King Minos’ labyrinth in Crete.

Before taking flight, Daedalus warned Icarus: Don’t fly too high, or the sun will melt the wax; don’t fly too low, or the sea’s moisture will weigh you down.

But Icarus, intoxicated by the thrill of soaring through the air, climbed too close to the sun. His wings melted, and he plummeted into the sea.

Beyond a simple moral fable, the story hints at a deep cultural awareness of aerodynamics—long before humans even attempted flight.

The Mysterious Flying Machines of Ancient India

Ancient Hindu texts describe Vimanas—mythological flying palaces or chariots said to soar through the skies with divine power. Some accounts, particularly in the Ramayana and Mahabharata, go into startling technical detail, describing propulsion systems and aerial battles.

Are Vimanas pure myth, or do they hint at lost knowledge? Historians debate their origins, but the detailed descriptions continue to fuel speculation.

Wan Hu’s Rocket Chair: The Man Who Tried to Reach the Stars

In the 16th century, Chinese official Wan Hu dreamed of reaching the stars—not with wings, but with 47 gunpowder rockets strapped to a wooden chair. According to legend, he lit the fuses, and in a deafening explosion, he vanished without a trace. While likely folklore, Wan Hu’s story endures as a symbol of humanity’s relentless ambition for flight and space travel.

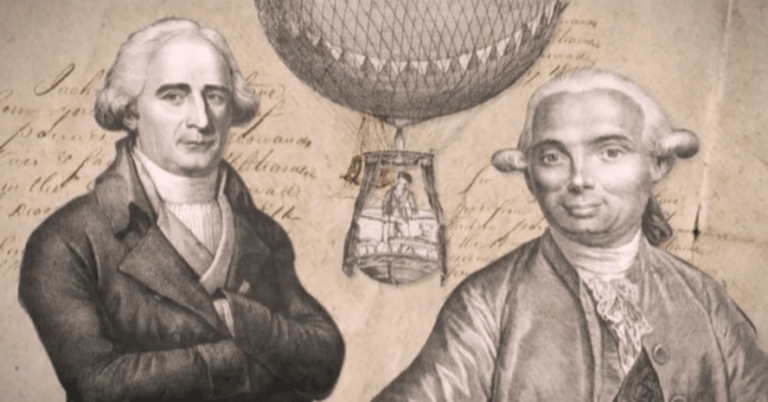

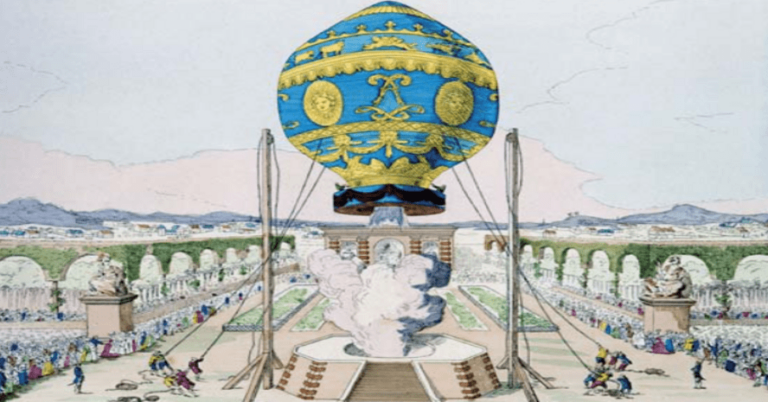

The First True Flight: A Balloon Over Paris

Imagine the hushed anticipation of the Parisian crowd on November 21, 1783. Their eyes locked skyward as a great billowing sphere—its golden-brown fabric swollen with heated air—trembled in place. Then, with a rush of excitement, it lifted from the ground. The first untethered, manned hot air balloon flight was underway. Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and François Laurent d’Arlandes, clad in fine coats and powdered wigs, clung to their wooden gondola as they ascended into the unknown.

What must it have felt like? To become the first humans in recorded history to truly leave the earth—not just as passengers, but as pioneers?

Perhaps they weren’t the first. “In our search for something of any substance, we came across a French source which tells of a missionary who once found, in archives in Peking, a report of the way the civilized nations of the east solved the problem of aerial navigation by means of balloons, centuries before the Europeans.” (Balloons and Airships, 1783-1973, Kenneth Munson & Lennart A. T. Ege, 1973). If this account holds any truth, then the Montgolfier brothers’ famous balloon was not an unprecedented marvel, but a rediscovery of an ancient achievement lost to time.

What we do know is that from that first flight in 1783, humanity became fixated on the sky.

And soon, we would not just rise into the air.

We would learn to steer it.

The Strange and Wonderful Birth of the Airship

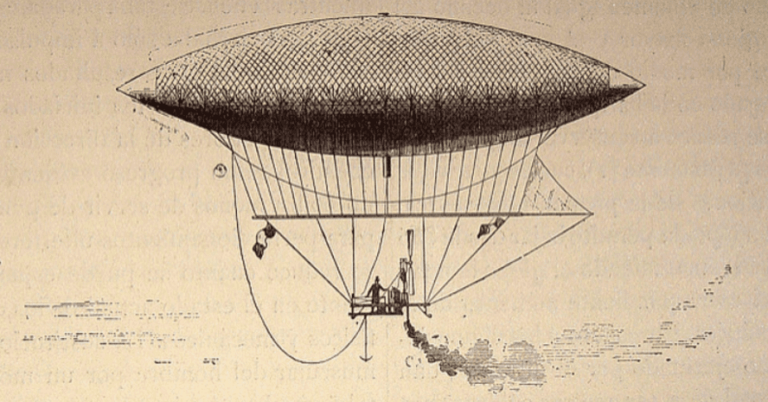

Fast-forward to 1852. A man named Jules Henri Giffard, a French engineer, piloted something even stranger than a balloon—an elongated, cigar-shaped vessel filled with hydrogen, fitted with a steam engine, and capable of movement on command. It was the first airship.

Giffard’s flight from Paris to Élancourt was slow, only reaching about 6 miles per hour. But speed wasn’t the point. For the first time in human history, someone had controlled flight—turning the sky from a wild, unpredictable realm into something navigable.

This was the spark. Over the next few decades, inventors from France, Germany, and America refined the airship’s design, pushing its capabilities further.

The Era of Giants: The Zeppelin Revolution

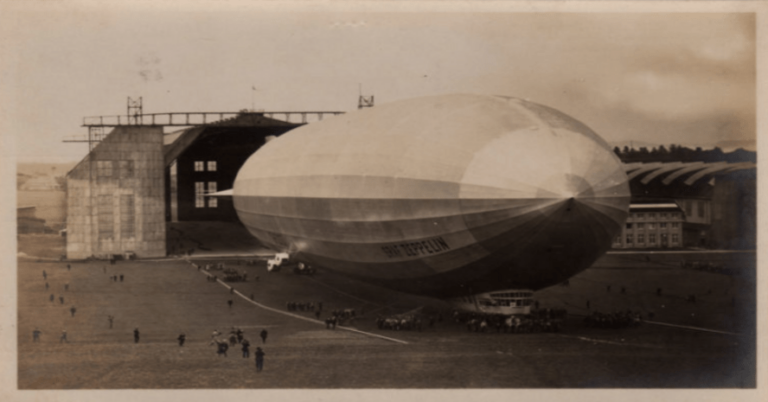

If Giffard’s airship was a crude first draft, Zeppelin’s designs were a masterpiece. By the early 20th century, his rigid airships—mammoth frames covered in fabric and filled with hydrogen—became the first true sky cruisers. And soon, they weren’t just for experimental flights. They became a spectacle.

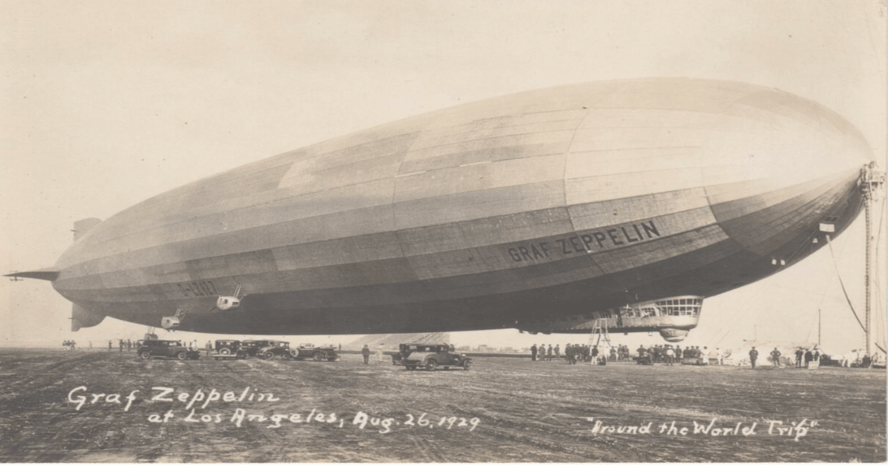

The Graf Zeppelin, launched in 1928, was the crown jewel. This floating leviathan was 776 feet long, nearly the length of three football fields. It could carry dozens of passengers in relative luxury, with smoking lounges, dining rooms, and panoramic windows offering views no human had ever experienced before.

And in 1929, it accomplished something breathtaking.

The Graf Zeppelin circumnavigated the globe.

This wasn’t a simple jaunt across a continent—it was an airborne odyssey that took 21 days, covering 20,000 miles. From New Jersey to Germany, over the Soviet Union, down through Japan, across the Pacific, touching California, and back again.

Imagine sitting aboard that ship, watching the vast Pacific stretch beneath you—an endless expanse of blue, interrupted only by the occasional island. Imagine seeing the lights of San Francisco flicker in the distance, then drifting onward, high above a world that barely understood what you were.

In an era where ocean liners took weeks to cross the Atlantic, this was magic.

The Golden Age of Airships

For a brief, shining moment, the airship reigned supreme. These floating giants became celebrities of the sky, drawing crowds as they hovered above world fairs and city centers. The Graf Zeppelin alone completed nearly 600 flights without a single fatality.

Passengers aboard these great vessels experienced something surreal—floating through the sky not in cramped cabins like modern airplanes, but in spacious lounges, sipping champagne as the world rolled by below.

And yet, just as quickly as it began, the age of airships flickered and faded.

The Vanishing of the Airship Dream

By the early 1930s, the world was shifting. Beneath the grandeur of airships, tensions were brewing on the ground—scientists, thinkers, and even passengers of these great sky vessels were beginning to sense the tremors of something darker.

In 1933, Albert Einstein fled Germany, leaving behind a country that had once celebrated him. That same year, the Graf Zeppelin continued its voyages, gliding over crowds that had no idea their world was about to change forever.

And then came the Hindenburg disaster in 1937—the fiery death of the world’s largest airship. The image of its destruction became the defining moment for airships, overshadowing decades of innovation.

But here’s the strange part.

Airships didn’t have to disappear. Hydrogen was dangerous, yes, but had airships switched to helium earlier, would the sky still be dotted with these floating giants today? Imagine a world where massive, silent airships still drift across the sky, offering slow, luxurious voyages over oceans and continents.

It’s a future that nearly existed.

Final Thoughts: A Future Lost in the Clouds

Manned flight took many forms after the first balloon lifted off in 1783. But there was something uniquely romantic about airships—massive, mysterious, and stately, floating like dreamlike behemoths above the world.

The airship’s story is not just one of invention, but of a road not taken.

What if airships had continued to evolve? What if the sky still belonged to these giants? What would travel look like today if we had pursued airship innovation rather than abandoning it?

The world may never know.

But sometimes, looking back at the past, you can’t help but wonder—what else have we forgotten?