The Walam Olum, once considered a significant Native American historical document, has been debunked as a fabrication. However, recent genetic studies have revealed intriguing connections between Native American populations and ancient Turkic peoples like the fabricated works detailed, suggesting there may really be a shared ancestry that predates known migrations.

The Walam Olum: From Revered Chronicle to Debunked Hoax

In the early 19th century, Constantine Samuel Rafinesque, a naturalist and linguist, introduced the world to the Walam Olum, which he claimed was an ancient Lenape (Delaware) Native American chronicle. According to Rafinesque, this document detailed the migration of the Lenape from Asia to America, their encounters with mound-building civilizations in the Midwest, and their eventual settlement along the Delaware River. The narrative appeared to support theories of Native American origins and migrations, aligning with the idea that indigenous peoples had traversed the Bering Strait from Asia.

However, scrutiny over time revealed inconsistencies and a lack of corroborative evidence. Rafinesque’s account of acquiring the Walam Olum was vague, and the original wooden plaques he described were conveniently lost, preventing independent verification. Linguistic analyses uncovered anomalies in the text, such as the presence of English idioms that had no equivalents in the Lenape language. Further investigations demonstrated that Rafinesque had likely crafted the narrative himself, influenced by his own theories and the limited knowledge of Native American cultures at the time. By the late 20th century, scholars like David Oestreicher conclusively demonstrated that the Walam Olum was a hoax, discrediting it as a legitimate historical source.

Scientific Evidence and the Turkic Connection

While the Walam Olum has been debunked, genetic research has shed light on real ancestral links between Native Americans and ancient Turkic populations. For a frame of reference, some of the most notable modern Turkic ethnic groups include the Altai people, Azerbaijanis, Chuvash people, Gagauz people, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz people, Turkmens, Turkish people, Tuvans, Uyghurs, Uzbeks, and Yakuts.

DNA studies suggest that some indigenous groups in North America share genetic markers with ancient populations from Central Asia, including regions historically inhabited by Turkic peoples. This supports the widely accepted theory that the ancestors of Native Americans migrated from Asia, likely across the Bering Land Bridge during the Ice Age.

Notably, research published by DNA Consultants highlights the presence of haplogroups common in both Native American and Turkic populations. These findings indicate deep ancestral ties, reinforcing the idea that indigenous American populations are part of a broader migratory story that connects them with ancient Eurasian groups. This does not support the Walam Olum‘s fabricated narrative but instead aligns with credible anthropological and genetic evidence.

Beyond the Hoax: The Continuing Search for Ancestral Truths

The Walam Olum serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of fabricated history, yet it also underscores the importance of ongoing scientific inquiry. While Rafinesque’s document was a hoax, the real genetic and historical ties between Native Americans and their ancient ancestors remain a fascinating area of study. Advances in genetic research continue to refine our understanding of early human migrations and cultural exchanges.

This is just my personal speculation, but perhaps Rafinesque really was onto something, and there was a source of truth in this migration story of the Lenape people. In his desperation to win a contest and get his ideas out there, he may have created this fabrication to make a quick push. Bad idea, good intentions?

Rather than relying on questionable historical accounts, modern research using DNA evidence, archaeology, and linguistic studies continues to uncover the true story of indigenous ancestry. The mystery of human migration remains an evolving field, reminding us that history is far more complex and interconnected than early 19th-century scholars could have imagined.

Let’s go deeper…

The Oghuz people, a historical Turkic group, have been linked to various ancient migrations, and some DNA studies suggest a distant connection between certain Indigenous American groups like the Lenape and these Turkic ancestors.

Who Were the Oghuz People?

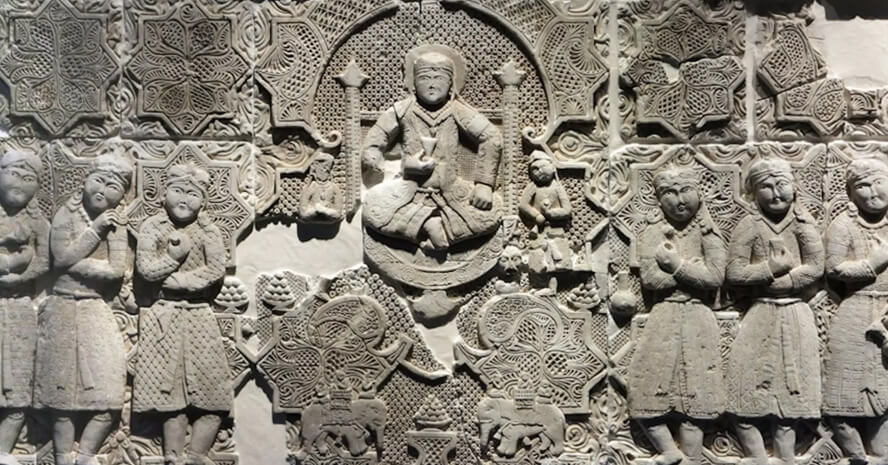

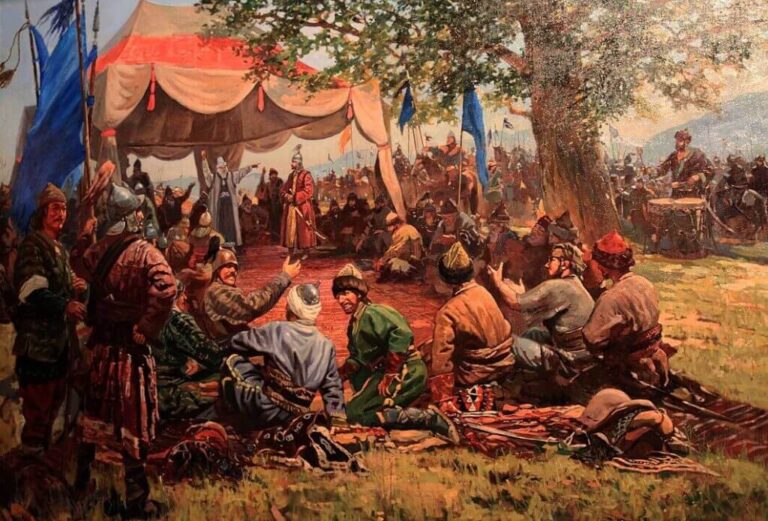

- The Oghuz Turks were a confederation of nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples who lived in Central Asia and later spread into Anatolia (Turkey) and Persia (Iran).

- They are the ancestors of modern Turkmen, Turks, and other Turkic groups.

- The Oghuz were known for their warrior culture, skilled horse riding, and advanced metallurgy.

Technology and Innovations

- Steppe Warfare: Mastered the use of the composite bow, cavalry tactics, and horse-based combat, making them dominant in battle.

- Nomadic Engineering: Built yurts (portable dwellings), which allowed them to migrate efficiently while maintaining an organized society.

- Metalwork & Armor: Crafted iron and steel weapons, including swords and armor, which played a role in their expansion.

- Trade and Diplomacy: Controlled parts of the Silk Road, connecting cultures and technologies between East and West.

Possible Connection to the Lenape and Indigenous Migrations

Some genetic studies indicate deep ancestral ties between Siberian, Turkic, and some Indigenous American populations. While there’s no direct link between the Oghuz and Lenape confirmed yet, the broader Turkic-Siberian migrations could mean that some cultural or technological influences spread before the Lenape emerged as a distinct group.

Timeline of Migrations and Cultural Development

To understand the possible connections between the Oghuz people, the Moundbuilders, and the Lenape, it’s important to establish a clear timeline of their historical presence and movements.

Prehistoric Migrations and Early Civilizations

- ~30,000–16,000 BCE: The first humans cross from Siberia into North America via the Bering Land Bridge. These early Paleo-Indians spread across the continent, forming diverse cultures over thousands of years.

- ~10,000 BCE: The earliest mound-building cultures in North America begin to appear, with hunter-gatherers creating earthworks for ceremonial and burial purposes.

Moundbuilder Cultures (Adena, Hopewell, Mississippian)

- Adena Culture (~1000 BCE–200 CE): Early mound-building societies arise in the Ohio Valley, leaving behind burial mounds and trade networks.

- Hopewell Culture (~200 BCE–500 CE): Expands upon the Adena’s earthworks, creating massive geometric mounds, engaging in long-distance trade, and developing ceremonial centers.

- Mississippian Culture (~800–1600 CE): The last major mound-building civilization, known for city-like settlements (such as Cahokia) and complex social structures. This culture declines before European contact, leaving a power vacuum in the region.

Oghuz Turks and Their Expansion

- 6th–8th century CE: The Oghuz Turks emerge as a distinct group within the larger Turkic migration in Central Asia, forming powerful nomadic confederations.

- 9th–10th century CE: The Oghuz migrate westward, settling in regions that include present-day Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Iran.

- 10th–11th century CE: Oghuz groups (such as the Seljuks) move into Persia and Anatolia, influencing the cultures they encounter.

Lenape Migration and European Contact

- Before 1000 CE: The Lenape (Delaware) people begin forming as a distinct Algonquian-speaking group, possibly originating in the Great Lakes or Ohio Valley region before migrating eastward.

- ~1200–1500 CE: The Lenape settle in the Mid-Atlantic region (modern Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware), where they establish villages and trade networks.

- 1609 CE: The first recorded European contact with the Lenape occurs when Henry Hudson sails into what is now New York Harbor.

This timeline helps connect the movements of early American Indigenous groups with the spread of Oghuz Turkic cultures, showing where potential links might have occurred through ancient migrations or shared ancestry.

To tie this all together now, let’s look at the end of the last Ice Age (~12,000 BCE – 9,000 BCE) when the Turkic region—spanning modern-day Siberia, Central Asia, and parts of Mongolia—was undergoing dramatic climate and ecological shifts that shaped early human populations. Here’s what was happening during this critical period:

Climate & Environmental Changes (~12,000–9,000 BCE)

- The Ice Age was ending, causing glaciers to retreat across Eurasia. This transformed the region’s climate from an icy tundra to grassland steppes, which would later become the heartland of Turkic nomadic cultures.

- The formation of major rivers and lakes, such as the Ob, Yenisei, and Amu Darya, created new fertile areas for human settlement and migration.

- The Altai-Sayan region (modern Siberia and Mongolia) became a key area for early human activity. Archaeological evidence suggests hunter-gatherer groups lived there, eventually giving rise to the first nomadic societies.

Human Presence & Cultural Development (~10,000 BCE–5,000 BCE)

- Early Proto-Turkic Ancestors:

- The people living in the Altai Mountains and Central Asia at this time were hunter-gatherers with advanced survival skills.

- They likely spoke an early proto-Altaic language, which would later branch into Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic languages.

- Technology & Tools:

- Microlithic tools (small stone blades) were widely used for hunting.

- The domestication of dogs occurred, aiding in hunting and protection.

- Possible Migrations Toward North America:

- Genetic studies suggest that some populations from Siberia migrated eastward, crossing the Bering Land Bridge into North America.

- The Denisovans, a now-extinct human species found in Siberia, may have interbred with early Native American ancestors, influencing their genetic makeup.

The Transition to Proto-Turkic Nomadic Life (~5,000 BCE)

- As the climate stabilized, early pastoralism began. These people started herding horses, sheep, and cattle, setting the foundation for the later Turkic nomadic empires.

- By 3,000 BCE–2,000 BCE, the region saw copper and early bronze tools, as well as increased trade with surrounding civilizations (such as early Chinese and Indo-European groups).

This era set the stage for the rise of the Turkic peoples, whose later expansion (~500 CE onward) would shape Eurasian history. If there is a genetic or cultural connection between early Turkic populations and Indigenous Americans, it may trace back to this deep ancestral link.